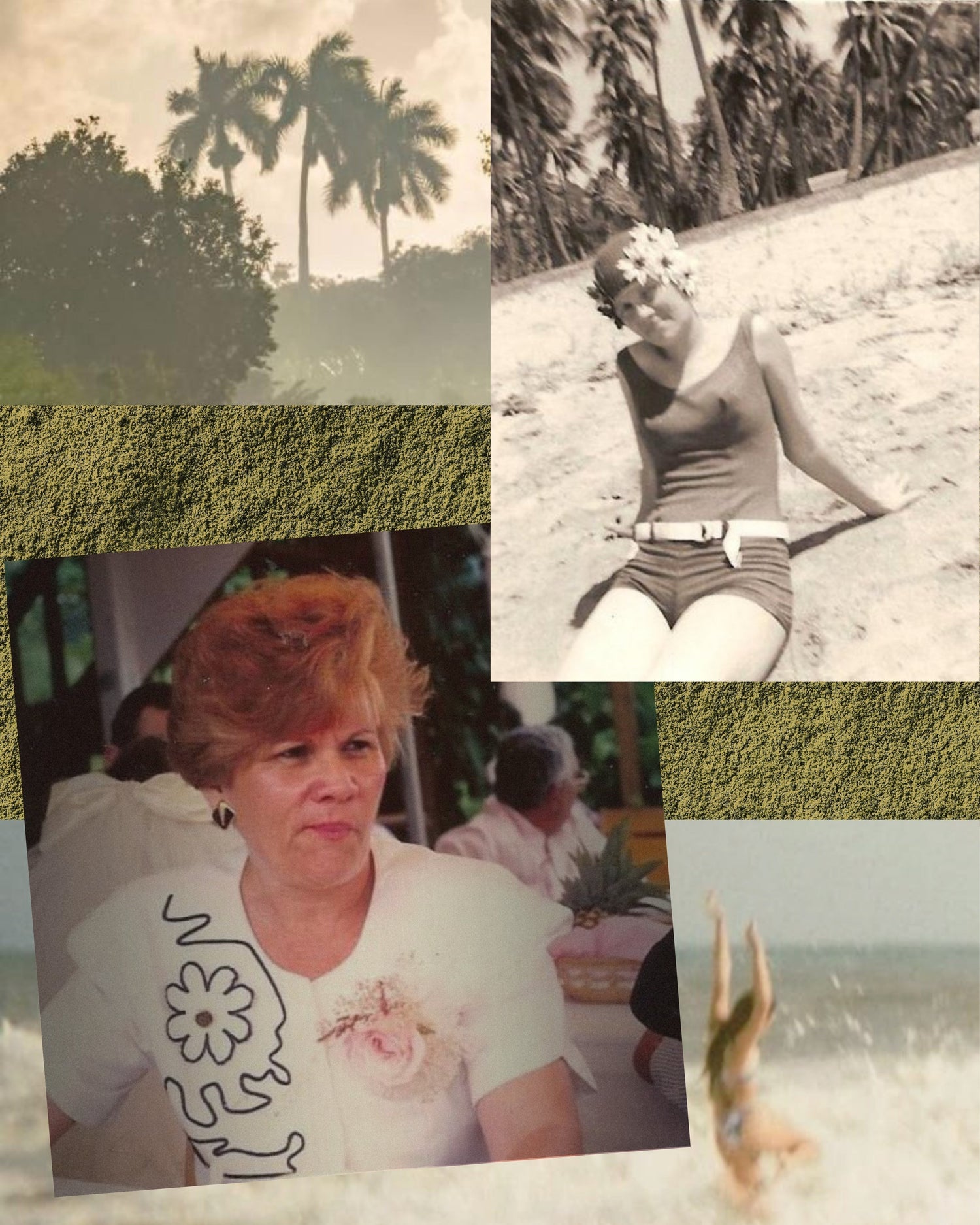

I didn’t learn beauty from my mother— not in the way it’s often passed down, as a ritual, a bonding moment, mirrored intimacy. What I learned from her was something else entirely: sacrifice, resilience. My mother was always working, sometimes two or three jobs depending on the season, and any attention she gave to herself was brisk, mechanical, necessary. Back then, I mistook that distance for disinterest. I understand now: it was devotion. To her family. Her selflessness came at the cost of softness.

And yet, she still found ways to have her moments. Matching outfits. Gold jewelry. A swipe of lipstick before stepping out. Her beauty wasn’t performative— it was practical, quiet, purposeful. It was never a ritual, but it was a presence.

My grandmother— her mother— was different. With her, beauty was ceremony. I would perch on the edge of her bed, mesmerized, as she massaged fragrant creams into her skin, layered perfumes like soft armor (pa’ beso, pa’ abrazo y pa’ por si acaso), and applied powder with gentle precision. To her, beauty was presence. It was self-respect. It was joy.

Growing up Latina, I watched women I loved and admired live within the liminal space between maintenance and indulgence. Beauty wasn’t just about how we looked; it was how we asserted our presence in a world quick to overlook us. In Latin America, beauty has always been more than skin deep— it’s an identity marker, a cultural practice, an inheritance. Still, inside the same home, beauty could inspire pride or provoke tension. One woman might see a bold red lip as empowerment, while another sees it as frivolity. The duality is real. One woman’s luxury is another’s obligation. We learned early that beauty came with conditions.

My father emphasized hygiene, respectability, modesty. So from him I learned to be quiet. I became fluent in restraint. But beauty always found its way in— through the scent of violet water, the rhythm of my grandmother’s prayers as she brushed her hair, the quiet elegance of a well-pressed skirt. It lived in textures, colors, and the way women carried themselves.

As a founder of a beauty brand, I now sit in reflection, often at the intersection of memory and identity. My relationship to beauty has been one of slow reclamation. I didn’t inherit beauty rituals through instruction, but through osmosis— through observation and admiration. And now, as an adult, I’m crafting something new from those fragments. Something that feels like both reclamation and evolution.

Latin American beauty is a complex tapestry. Our histories are woven with indigenous plant wisdom, African healing traditions, and colonial inheritances. From aloe vera and coffee scrubs to ceremonial braids and sugar waxes, beauty has always been intertwined with culture. Over the decades, Western beauty ideals infiltrated our standards— lighter skin, looser curls, sharper noses. Yet our communities have always found ways to push back, to reimagine, to reclaim.

In Skin: A Natural History, Nina Jablonski writes that our skin is a living record of our lives— a canvas of climate, culture, and continuity. For Latinas, our skin tells stories of migration, of resilience, of resistance. When we tend to it, we’re doing more than pampering; we’re preserving. We are honoring. We are tending to something ancestral.

In this political climate, where uncertainty and exclusion threaten to flatten our stories, beauty can feel complicated. Because we are constantly told— in policies, in headlines, in micro-aggressions— that our visibility is conditional. That our safety, even our belonging, is up for debate.

What if we embraced beauty as our abuelas did? With grace. With dignity. Without apology. What if our routines— our oils, our rituals, our perfumes— were not just about appearance, but about identity and endurance? What if beauty was less about being accepted and more about honoring where we come from?

Lately, I’ve been choosing to take up space again. Not out of defiance, but out of reverence. For the women who never had the time. For the girls learning to love themselves in a world that questions their worth. For the ancestors who endured, and the future ones who will thrive.

Because for us, beauty is not a distraction. It is a legacy. A soft, deliberate protest. A return.

So maybe the question isn’t whether beauty matters.

Maybe it’s this: How do we make space for softness, for ritual, for joy— even when the world tells us to be hard? How do we stay visible in a world that asks us to disappear?

And how do we love ourselves like our abuelas prayed we would?